The architect of the Courthouse, Charles F Schweinfurth approached both Brangwyn and Maxfield Parrish to produce murals, but the latter pleaded overwork and ill health. His place was taken by a Miss Violet Oakley of Philadelphia, who painted the American Constitutional Convention of 1787 in the lunette opposite Brangwyn’s.

A contract was drawn up and signed on 14 August 1911 in the sum of US$20,000. It is interesting to note that as late as the 1930s Brangwyn was working without contracts for clients in Britain, which frequently led to problems – The Brits belived in gentleman’s agreements – the Americans were probably more sensible.

Brangwyn agreed, under the terms of the contract: ‘to ensure historical accuracy in ‘dress, action and portrait’; ‘to visit the site and location’ before embarking on the commission; ‘before and after it has been set in place [to] personally visit the site, and touch up or finish this painting in place’.

Although the costumes are vaguely historical and the portraits are assumed likelike from contemporary descriptions and portraits, it is highly doubtful whether Brangwyn ever intended visiting America. Brangwyn also agreed that, once the original scheme was accepted, he would ‘deliver’ the finished work within fifteen months – it took 4 years!

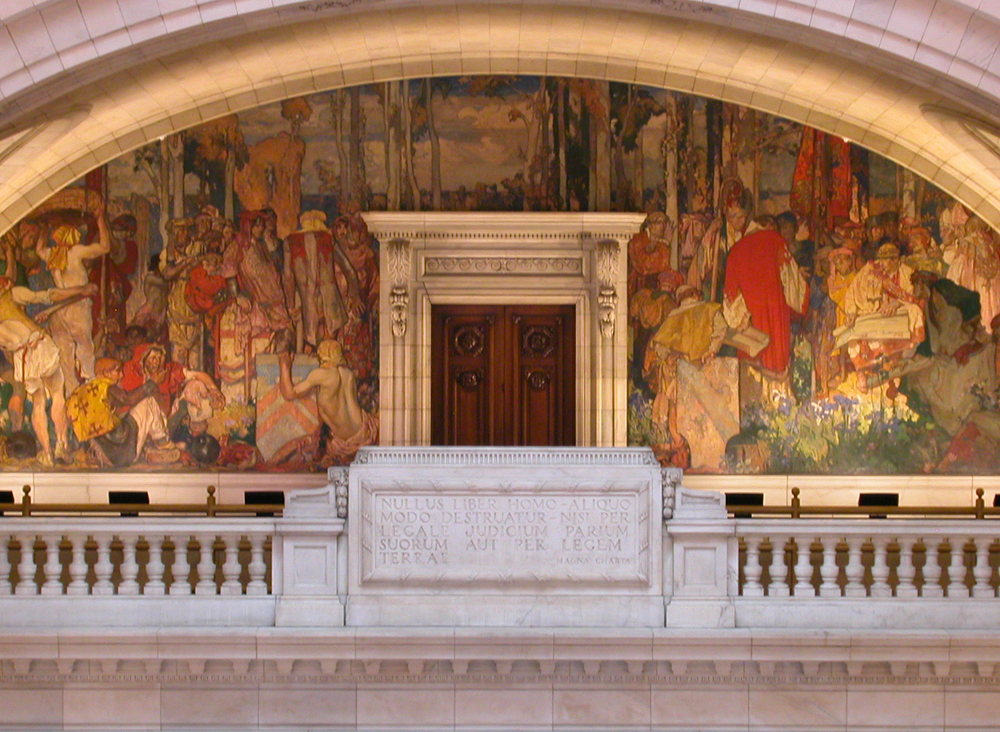

The City leaders chose a very English subject for their mural, King John Signing Magna Carta. Structural unity is gained by strong verticals of tree trunks. King John is seated on the right debating inwardly whether to accede to the nobles, watched by clergymen and retainers. Stephen Langton, in a rich orange-red robe stands next to the King, and in front of him sits Robert Fitzwalter holding the parchment. The Earl of Pembroke and Pandulph, the Pope’s legate, stand behind the King. On the left the Barons stand imperiously, their looks threatening and defiant, whilst half-nude boatmen bring provisions, and soldiers guard a chest of documents. Runnymede, where the meeting took place, is a strange area, a water-meadow but wide enough to accommodate a large crowd of people, horses, attendents. It was apparently chosen because the Barons wanted a neutral meeting place, it was close to the river for transport and between the royal fortress at Windsor Castle and the rebels’ stronghold at Staines.Most of the figures, unusually for Brangwyn, are static, but still convey great strength.

Unfortunately Brangwyn didn’t appreciate that a large doorway would cut his mural in half so he had to redesign the grouping of nobles etc.

The New York Times stated that the canvas was the ‘largest picture ever painted in London for shipment abroad’. The Studio magazine noted that the work was ‘carried through without any collaboration on the part of assistants’ – highly unlikely but Brangwyn probably thought that’s what his American clients would wish to hear!

For an associated study click here and Knight.

Literature: Galloway, 1962 p73. The Studio, p3-4 Vol 63, November 1917, Finch, ‘Recent Decorative Work of Frank Brangywn ARA. I. Mural Paintings in the Panama-Pacific Exposition’. Furst, 1924 p95-108. Rodney Brangwyn, Brangwyn, William Kimber London 1978 p162-166. Neuhaus, The Art of Exposition, Paul Elder & Company San Francisco. Shaw-Sparrow, 1919, p212. San Francisco Examiner, Exposition Edition, 20 Feb 1915.

Illustrated: Galloway, 1962 plate 36, portion of Industrial Fire. San Francisco Examiner, Special Exposition edition, 20 February 1915 (two of the panels in colour on front page, Air and Dancing the Grapes). The Studio, p6-10, Vol 63, November 1917, Finch, ‘Recent Decorative Work of Frank Brangwyn ARA. I. Mural Paintings in the Panama-Pacific Exposition’. Furst, 1924, p97, 98, 101, 102 facing p95. Amelia Defries, ‘Frank Brangwyn RA, Master Craftsman’, American Magazine of Art, November 1924 11 Vol. 15p558 detail from Windmill.